.

BREAK FREE FROM THE WEIGHT YOU'VE GAINED

Stop overeating, eliminate cravings, break sugar addictions and stop stress eating

with the latest discoveries in neuroscience.

The Online Weight Loss Class Developed By Neuroscientists

SOLVE THE PROBLEMS THAT CAUSED YOUR WEIGHT GAIN

What would happen to your weight if you stopped overeating, eliminated or significantly reduced out-of-control cravings, broke your addiction to sugar, cut your hunger in half, and developed intense cravings for fruits and vegetables?

You would lose a considerable amount of weight without the misery of dieting.

But how do you solve intractable problems like stress eating?

In the last few years there's been a revolution in our understanding of the brain's role in creating the habits and behavior that cause weight gain. This new understanding allowed neuroscientists to develop techniques and behaviors to painlessly solve these problems.

Take hunger, for example. There's a vast literature in peer-reviewed science journals showing which protocols cut hunger and why they work.

For example, a simple technique involving memory can reduce your hunger for the next meal by up to 50%. Neuroscientists call it "The Meal-Recall Effect."

Imagine how much weight you'd lose if you solved the problems that prevent you from reaching your goals?

Our online class, developed by neuroscientists, can turn your imagination into reality.

LOSE WEIGHT WITHOUT THE MISERY OF DIETING

Our video-based online course shows you how to use the latest discoveries in neuroscience to free yourself from the problems that keep you chained to your weight.

By the time you complete this course you will know how to

stop binging and overeating, end sugar addiction, eliminate or reduce out-of-control cravings, cut your hunger in half and develop intense cravings for healthy food.

All using evidence-based techniques published in neuroscience journals.

In fact, every lesson ends with academic citations so you can see the science it's based on.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN

We will teach you the skills to break the eating habits responsible for your weight gain, remove the obstacles blocking your goals and lock in new mindsets, behaviors and patterns that result in weight loss.

You can use these skills to:

- Stop binging or overeating

- Eliminate or weaken out-of-control cravings

- Cut your hunger by up to 50%

- Break your addiction to sugar

- Develop intense cravings for healthy food

- Eat smaller portions without feeling deprived.

- Create healthier eating habits and patterns

- Stop using food as a coping mechanism

- Develop a healthy relationship to food

- Get more pleasure out of food than you're currently getting

MAIN BENEFIT

Lose weight without the misery of dieting.

SECONDARY BENEFITS

- Regulate blood sugar levels

- Stabilize your mood

- Increase energy levels

- Reduce cholesterol

- Improve heart health

- Reduce inflammation

- Less "brain fog"

- Reduce diabetes risk

- Reduce belly fat

IS THIS COURSE FOR YOU?

Yes, if you've tried multiple diets, failed to keep the weight off, and want an evidence-based alternative that doesn't require deprivation.

You don’t need willpower or self-control to succeed in this class because the techniques you’ll learn don’t require them. All you need is a willingness to learn and trust the science this course is built on.

COURSE SET-UP

- Video, text, guides and downloads

- 21 sections, each with 3 lessons

- Course is about 12 hours long but most students space it out over 4 weeks to absorb the insights and apply the techniques.

- Each lesson under 5 minutes

- Each lesson ends with linked citations to help you identify the research and locate scientific sources

- VIP support--you can ask the instructor questions via personal coaching, email, and “office hours.”

The Neuroslim Class

$299

Watch our 5 Min Video

Find Out How You Can Lose Weight With Techniques Developed By Neuroscientists

HAVE YOU GAINED WEIGHT BECAUSE OF YOUR FOOD CHOICES OR YOUR EATING HABITS?

Are sweets causing your weight gain or is it that you never developed the habit of using 'friction' or "guard-rails" that prevent overeating?

Is pizza making you fat or is it that you've developed the habit of ignoring internal satiety signals that make it easy for you to overeat?

Is pasta and bread causing your weight gain or is it the habit you've developed of using food as a coping mechanism?

Are hamburgers and fries making you gain weight or is it that your eating habits artificially inflate your hunger for fast food?

Are sodas and juices causing your weight gain or is it a sugar addiction that habituated your intake from a can every other week to 5 a day?

Is fried food causing your weight gain or is it that you haven't developed a system to manage your cravings?

Are those sweets making you fat or is it that you've habituated your body to need more and more sugar to feel satisfied?

Are processed foods making you fat or is it that you don't know the techniques to weaken cravings for unhealthy food?

FOOD DIDN'T CAUSE YOUR

WEIGHT GAIN AS MUCH AS THE HABITS YOU DEVELOPED TO EAT IT.

Research shows you’d lose more weight by changing your habits than dieting. But how do you break fat-promoting eating habits like overeating?

With techniques and insights ripped right out of the science journals, our online class will teach you how.

Developed by neuroscientists, our course teaches you how to stop overeating, break sugar addictions, cut hunger, quit sodas and more.

The Neuroslim Class

$299

⇧ WATCH A SAMPLE LESSON

Our course is made up of captivating videos, informative screencasts, text, charts, group conversations, and downloads.

Lose Weight With A Science-Backed Alternative To Dieting

We analyzed thousands of peer-reviewed studies from the most important neuroscientists, extracted their most important discoveries and turned them into an easy-to-follow weight loss program.

Here's what you'll be able to do in our online weight loss class:

CONTROL YOUR CRAVINGS

How do you stop craving unhealthy foods? How do you resist foods that are bad for you when they’re everywhere and billions are spent marketing them? How do you stop impulse eating?

We answer all of these questions and more. Best, you'll learn two craving-control techniques that are so effective, they regularly eliminate 20-25% of total caloric intake for the people who use them. These techniques are based on the pioneering work of psychologist Walter Mischel's "The Marshmallow Experiments."

They're practical, easy to use, and give you a sense of complete mastery of your cravings.

EAT LESS WITHOUT FEELING DEPRIVED

If you simply ate less food--even without changing your diet-- you’d lose weight. But how do you do it when you’ve become used to eating a large amount of food?

We’ll teach you how to feel completely satisfied with less food by:

- Applying the “subsiding pleasure” approach neuroscientists developed out of their research on Sensory Specific Satiety (the decline of food's pleasure with each bite).

- Exploiting psycho-physicist Josef Delboeuf's discovery of the brain's blind spots. The brain can be easily fooled into faster satiety if you understand--and act on--the limitations of the visual cortex.

- Using the results of a Harvard experiment that proved "imagined eating" can reduce actual consumption.

EAT HEALTHIER

How can you eat healthier without forcing yourself to eat what you don’t like? How do you motivate yourself to cook something healthy? How do you strike a balance between eating healthy and making room for comfort food? You’ll learn:

- Neuroscientific techniques that train your taste buds to love healthy food.

- How the Nutrilicious concept can make you crave apples the way you crave donuts.

- How the latest science in “acquired tastes” can help you crave fruits and vegetables.

REDUCE PORTIONS

What would happen to your weight if, instead of dieting, you simply reduced your portions? What if you could be just as content eating 3 Oreos as you are eating 12 or more? The problem with reducing portions is that it can create the same feelings of deprivation that dieting does. Or even low-grade panic attacks!. How do you get around that? With…

- Evidence-based techniques that slowly reduce portions without suffering.

- Strategies capitalizing on “The Portion Size Effect,” a phenomenon that influences how much or how little can satisfy us.

- Methods the French use to be completely satisfied with smaller portions.

REDUCE HUNGER

Are you hungry all the time? How do you deal with overwhelming hunger pangs? Does the slightest exposure to food (ads, passing fast food establishments) make you hungry? Neuroscience has developed proven ways to dramatically reduce hunger, including:

- Methods that significantly reduce what researchers call “food cue reactivity.”

- The use of a groundbreaking discovery in neuroscience--The Meal-Recall Effect--a finding that proved memory has a profound impact on hunger.

- Improvements in how you present food (believe it or not, the more pleasing the presentation THE LESS FOOD YOU’LL WANT.

The Neuroslim Class

$299

Meet Some Of The People Who Chose Neuroscience Over Dieting

Total game changer!

After trying dozens of diets (and failing them) I know a LOT about the subject of dieting, but this class consistently and repeatedly surprised me with things I didn't about losing weight.

My skeptical nature was assuaged when I saw that every lesson ends with a list of academic citations showing which scientific studies the lessons were pulled from.

This class completely changed my eating habits and I'm starting to see major results from it. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED!

Jane Walker-Booth

New York

A home run!

The videos are sooooo well done, sometimes genuinely funny, but always informative. But more importantly, TRANSFORMATIVE.

I have changed almost every aspect of how I eat because of this class and I can see the dividends its paying through my wardrobe.

I've done Weight Watchers and Noom--neither came close to the effectiveness of this class' techniques.

Dewayne Williams

Houston

Completely changed my eating patterns.

Instructor is engaging and accessible. The personal coaching session was incredibly useful.

The emphasis on science (there must be over 200 citations peppered throughout the course) made me trust that this wasn't just some rando with misguided opinions.

There is simply nothing like this class--it will completely change your relationship to food.

Madelaine Taylor

Boston

STOP OVEREATING

You start off wanting an Oreo and you end up eating half the package. Why do you overeat even when you don’t want to? The Neuroslim class will teach you:

- The concept of “mindful satiation,” which is proven to tamp down overeating

- How to identify and neutralize hidden hunger associations you’ve built up

- How to build “guard-rails” that allow you to eat addictive food without binging

END STRESS EATING

How do you tell whether it’s hunger or stress driving a craving? How do you neutralize triggers to emotional eating? How do you stop eating to comfort yourself? How do you control compulsive eating behaviors? Neuroslim will teach you:

- What to do when you’re about to stress eat.

- How to stop using food as a coping mechanism.

- The 3 behaviors research says will stop or significantly decrease stress eating.

QUIT SUGARY FOODS

How do you say no to sweets without feeling cheated? How do you quit or cut back on sugar when it’s in everything? How do you quit a substance many neuroscientists consider a drug? Neuroslim will liberate you from sugar by:

- Using the same techniques drug addiction experts use to get people off drugs. Like “systematic discontinuation.”

- Using the concepts of “friction,” “roadblocks” and “guardrails” that allow you to eat sweets while protecting you from the addictive nature of sugar.

QUIT SUGARY BEVERAGES

Experts believe that sodas (including diet sodas) and juices are the single biggest culprit of the obesity epidemic. But how do you give up something you're basically addicted to? Neuroslim can help you by:

- Using the gold standard treatment used by addiction experts to get people off drugs.

- Using micro-techniques that have macro effects. For example, using taller, slender glasses rather than circular wide ones to drink sodas and juices (proven to significantly reduce the amount of sugary beverages you drink).

CHANGE BELIEFS THAT CAUSE WEIGHT GAIN

Acting on false beliefs can cause weight gain. Here are just some of the beliefs you’ll change in our class:

- Breakfast is the most important meal of the day.

- Weight loss cannot happen without eating healthy food you don’t like.

- You must resist temptation.

- You should finish what's on your plate lest you be wasteful.

- It’s better to eat a lot of small meals than three large ones.

- Weight loss requires you to give up comfort food like mashed potatoes, cake and ice cream.

- Weight loss should be fast and abrupt rather than slow and steady.

DEVELOP MINDSETS THAT PRODUCE WEIGHT LOSS

The Neuroslim class will cultivate several new mindsets:

- Your goal shouldn’t be weight loss but well-being. Because well-being produces weight loss.

- Changing eating habits and behaviors is the only way to permanently lose weight. You’ll see overwhelming evidence in hundreds of our academic citations.

- Dieting is a terrible way to lose weight. You’ll see systematic reviews of dieting’s stunning ineffectiveness (95% failure rate)

- Pleasure is not the enemy, it's the path to weight loss. You’ll see convincing evidence that people who get more pleasure out of food are thinner and healthier.

- Move away from a “Food as nutrients” to a “Food as well-being” consciousness. Without changing your definition of food you’re doomed to repeating the endless cycle of our toxic diet culture.

- Weight loss takes time. It took a long while to get to your current weight. Why would you think you could shrink in a few weeks what took years to expand?

- Trade urgency for permanency.

Instead of quick fixes we offer gradual adjustments that lead to permanent change. We’ll help you strike a bargain: A quick but temporary reduction in weight for a slow but permanent one.

EDUCATION THAT HELPS WEIGHT LOSS

Neuroscientists have upended our understanding of hunger, satiety and eating. You’ll learn counter-intuitive evidence that will accelerate your weight loss. For example:

- Bigger portions incentivize us to eat more. Most people think portions have grown because we’ve gotten hungrier. It’s the reverse. Our hunger has increased because the food industry made portions bigger. It’s called “The Portion Size Effect” and we show you how to get around it painlessly.

- Habituation, not dieting, is the unifying theory of effective, sustainable weight loss. For example, you didn’t start off drinking 5 cans of soda a day. You started off drinking a little, adapted, then increased the amount. Habituation helped you increase consumption to 5 cans a day and habituation can just as easily get you back to zero.

- The size, color, and shape of platters, plates, glasses, and utensils matter. They can make the difference between eating and overeating.

The Neuroslim Class

$299

Meet MORE People Who Chose Neuroscience Over Dieting

Total game changer!

After trying dozens of diets (and failing them) I know a LOT about the subject of dieting, but this class consistently and repeatedly surprised me with things I didn't about losing weight.

My skeptical nature was assuaged when I saw that every lesson ends with a list of academic citations showing which scientific studies the lessons were pulled from.

This class completely changed my eating habits and I'm starting to see major results from it. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED!

Jane Walker-Booth

New York

A home run!

The videos are sooooo well done, sometimes genuinely funny, but always informative. But more importantly, TRANSFORMATIVE.

I have changed almost every aspect of how I eat because of this class and I can see the dividends its paying through my wardrobe.

I've done Weight Watchers and Noom--neither came close to the effectiveness of this class' techniques.

Dewayne Williams

Houston

Completely changed my eating patterns.

Instructor is engaging and accessible. The personal coaching session was incredibly useful.

The emphasis on science (there must be over 200 citations peppered throughout the course) made me trust that this wasn't just some rando with misguided opinions.

There is simply nothing like this class--it will completely change your relationship to food.

Madelaine Taylor

Boston

YOU'VE TRIED DIETING

It's Time For Something New

OUR CLASS OUTLINE

Click To See What Techniques You'll Learn

-

Quit Sugar Like Addicts Quit Drugs

Here's a condensed outline of our Quit Sugar Like Addicts Quit Drugs section.

NOTE: All lessons end with links to the peer-reviewed studies they're based on.

SECTION 1: NATURE OF CRAVINGS & THE FORCES EXPLOITING THEM

Lesson #1 We're Wired To Overeat

Have you ever wondered why we start wanting a nibble of food and end up binging? Why do we overeat even when we don’t want to?

Few of us intend to hit food like a linebacker, yet almost all of us end up doing just that. Why? In this lesson, you’re going to learn a surprising conclusion drawn by evolutionary biologists: We are wired to overeat.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Get you to understand you don't binge on sweets because you lack self discipline or self-control. You overeat because you were designed to do so.

GOAL: Set you up to understand the next few lessons-- how the conscious brain can outsmart our instinct to overeat.

Lesson #2 Is Sugar A Drug?

We use the phrase "sugar addiction" in everyday conversation because our experience is eerily reminiscent of what we think of as drug addiction. You start eating, believing you're only going to eat a certain amount but once you start you can't stop.

You try to get a handle on it. You try to cut down but you repeatedly fail. There's a compulsive quality to it that can start to take on a life of its own.

Despite a strong motivation to stop you're unable to get consumption under control. But here’s a question--do scientists actually believe sugar is an addictive substance? The answers will surprise you.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand sugar's properties encourage disordered eating (overeating, binging). That between the addictive nature of sugar and our wiring to overeat we need to put "guard rails" around the consumption of sweet foods and beverages

GOAL: Awareness that sugar ignites our instinct to overeat in a way that no other food does. This is necessary to understand the "guard rails" we discuss later.

Lesson #3 How The Food Industry Exploits Our Instinctual Drive To Overeat

By ordering laboratory scientists to manipulate chemicals and food substances into their highest “bliss points,” food giants can knock down the natural guard rails we have to prevent overeating.

A natural craving for cookies might compel you to eat three or four. But the way they are manufactured compels you to eat eighteen. Basically, the food industry produces food designed to make us lose control.

And since three-quarters of the groceries we buy are processed food, we have a lot to lose control over. Here we discuss the science of how the industry makes processed food addictive.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Help you understand why it's so hard to control our eating around processed foods and why we have to protect ourselves from the industry’s predatory practices.

GOAL: Create a mindset shift that you can't approach eating sugary food the way you would, say, celery. Understand there are forces arrayed against you that have nothing to do with willpower and self-discipline.

SECTION 3: HOW TO STOP BINGING OR OVEREATING ADDICTIVE FOODS

Here you’re going to learn the most effective ways to stop binging on addictive foods. Centering around what neuroscientists call "food cue reactivity" you'll find amazing tips and tricks that will prevent you from overeating.

Lesson #1: "GUARD RAILS" THAT HELP YOU EAT ADDICTIVE FOOD WITHOUT BINGING

From common sensory cues that trigger overeating to serving styles that encourage binging you'll learn how unconscious eating behaviors set the stage for a loss of control.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Awareness of particular eating patterns, habits and behaviors that contribute to a loss of control.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: How to avoid behaviors that lead to binging and overeating and develop very specific "guard rails" that keep you safe while enjoying normal portions of addictive food.

Lesson #2: HOW TO CREATE MORE FRICTION AROUND ADDICTIVE FOODS

Again, we cannot approach a donut the way we would an apple. Here we investigate a concept known as "friction" that's proven to eliminate or significantly reduce overeating.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Awareness of how creating "friction" around addictive foods can practically guarantee you won't overeat

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: Dozens of tactics and strategies designed to stop you from overeating, not from enjoying food you love. They are a recognition that our instinct to overeat, the addictive properties of processed foods, and the industry’s exploitation of those properties all compel us to approach these unhealthy foods differently than we do healthy foods.

SECTION 3: FREE YOURSELF FROM SUGAR

Lesson #1: How Habituation Got You Hooked On Sugar

Nobody starts off eating a whole bag of Oreos or drinking a 64 oz Big Gulp of soda. We start off with a little (3 Oreos, 8 oz of soda, etc.), grow accustomed to it, then need a little more to get the same satisfaction.

Neuroscientists call this habituation (and its reinforcing partner, homeostasis). Here you'll learn how habituation and homeostasis work to create increased consumption.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how you got to your current point of sugar consumption.

GOAL: Understand that the same forces that got you to the current level of consumption--habituation and homeostasis--can be used to get you back to zero (or little) consumption.

Lesson #2 How To Use Habituation & Homeostasis To Break Your Sugar Addiction

Here we introduce the process Addiction Medicine uses to get people off drugs so we can apply it to sugar. It’s called “systematic discontinuation.”

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how experts get addicts off drugs without withdrawals.

GOAL: Get a fundamental understanding of the process so we can apply the dynamics to sugar in the next lessons.

Lesson #3 Applying "Systematic Discontinuation" To Sugar

You are going to learn the methods Addiction Medicine specialists use to get people off drugs and apply it to sugar. This is a step-by-step guide to "getting off sugar" the same way addicts "get off drugs."

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how the process works using your own problem foods you want to get off of (bag of cookies, 5 cans of soda, etc.)

Goal: Eliminate or significantly reduce (do you really want to live in a world without Oreos?) your sugar intake without feeling cheated or deprived.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: Step-by-step techniques that bust your sugar habit and keep it busted. These techniques do not involve deprivation and they do not require willpower, self-control or self-discipline.

SECTION 4: CAST YOUR NEW EATING HABITS IN CEMENT

Quitting sugar requires the establishment of new eating habits. It isn't difficult but it does take time. You will inevitably go through periods where you'll forget what to do, become resistant or sabotage yourself in some way.

In this section, we show you how to avoid the traps of building new eating habits by overcoming resistance, dealing with frustration and rebounding from failures.

Lesson #1: Awareness

Building new habits require you to pause and pay attention to what you’re thinking and doing. They require in-the-moment “sensors” that go off when you’re in the middle of a habit you’re trying to break, or a habit you’re trying to establish. In this lesson, you'll learn the art of "cultivating a witness state" so you can be more aware of what you're doing.

Lesson #2: Build "Emergency Reserves" For Setbacks

The latest studies in resilience show that a strategy called "Planning For Setbacks" dramatically increase accomplishment of goals. We'll show you how to apply this brilliant approach.

-

Cut Your Hunger In Half

Here's a condensed outline of our Cut Your Hunger In Half section.

NOTE: All lessons end with links to the peer-reviewed studies they're based on.

SECTION 1: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT HUNGER BEFORE YOU CAN REDUCE IT

By knowing what strategies the brain uses to navigate through its hunger matrix, cognitive scientists have discovered how to manipulate its circuitry and work its blind spots to aid weight loss. None of their strategies will make sense, however, without first knowing how the brain operates and that's what this section is about.

Lesson #1 Your Brain Decides How Hungry You Are--Not Your Belly

In the coming lessons, you're going to learn how to significantly reduce your hunger by working levers of the brain that control appetite and satiety. But in order to do that you need to understand a counter-intuitive aspect about hunger: It isn’t your belly that’s making you hungry; it’s your brain.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how the brain constructs hunger and satiety--where it gets its information, how it processes it and the blind spots that can be exploited to reduce hunger.

GOAL: Prepare you for the tools you'll use to cut your appetite.

SECTION 2: HUNGER CAN BE MANIPULATED UP OR DOWN

Hunger, according to neuroscientists, is a highly suggestible state that can be influenced by a variety of factors that have nothing to do with the emptiness of your belly. In this section, you're going to find out what they are and how to capitalize on them.

Lesson #1: HOW YOU ARTIFICIALLY INFLATE YOUR HUNGER WITHOUT KNOWING IT

Neuroscientists conceive of hunger as "organic" or “manipulated.” In the manipulated state, it doesn’t matter whether your belly is empty or full, or whether you have a biological need for fuel. You experience hunger because somebody or something brings it out in you. Spoiler alert: Our hunger is constantly being manipulated.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how your hunger can be trained up or down as a "conditioned response" to certain stimuli.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: How to avoid situations and behaviors that lead to artificially raising your hunger.

Lesson #2: FOOD'S ROLE IN CREATING HUNGER

Food doesn't just satisfy hunger; it can CREATE it. This is one of the more eye-opening discoveries in neuroscience and it's instrumental in guiding hunger-reducing behavior. Here you'll see stunning examples of how, if you're not careful, you can use food to create hunger that wasn't there originally.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how we inadvertently use food to stoke unnecessary hunger. Example: eating breakfast when you're not hungry. You take a nibble of toast, it sparks hunger, and next thing you know you have a full breakfast. But you started off with no appetite! Food created the hunger.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: Tactics and strategies that avoid conscious or unconscious manipulation of your hunger.

SECTION 3: HOW TO DECREASE YOUR HUNGER

Lesson #1: BREAKING HUNGER ASSOCIATIONS YOU DIDN'T KNOW YOU HAD

Hunger is often a conditioned response to stimuli (example: you're not hungry, you see an ad for pizza and suddenly you're hungry). Fortunately, you can use classical conditioning to break those associations. In this lesson, you'll see plenty of examples on how to do that.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand what it takes to break conscious and unconscious hunger associations.

GOAL: Create new eating behaviors that break weight-gaining hunger associations.

Lesson #2: THE MOST POWERFUL HUNGER REDUCTION TOOL

Memory has a huge influence on hunger and satiety. Known as "The Meal-Recall Effect," this is one of the most important discoveries ever made in our understanding of hunger. Here you'll understand how it came to be and what impact it has on your every day hunger levels.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how the brain uses memory to construct hunger and satiety.

GOAL: Awareness of how important it is to pay attention to what you're eating so your brain can recall it when it formulates hunger levels for the next eating opportunity.

Lesson #3 APPLYING "THE MEAL-RECALL EFFECT"

A step-by-step guide to applying this proven hunger-reducing technique. Taken directly from the methodology used in the peer-reviewed experiments, the steps are simple to understand and easy to implement.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Create strong memories of what you're eating so your brain can access those memories and influence how it perceives hunger for the next meal.

Goal: Create new ways of approaching your meals, enjoying them and "storing the data" your brain will use to perceive less hunger.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: How to activate "The Meal-Recall Effect" to produce the same results achieved in laboratory settings (a 14% to 50% reduction in hunger).

SECTION 4: EXPLOITING THE BRAIN'S BLIND SPOTS TO FURTHER REDUCE HUNGER

The brain processes visual information in a way that often produces optical illusions. The psychophysicist Joseph Delboeuf made this discovery when he experimented on optico-geometric visuals that came to be known as "The Delboeuf Illusion." Weight loss researchers have documented its effect on hunger reduction.

Lesson #1: WHAT IS THE DELBOEUF ILLUSION & HOW DOES IT APPLY TO HUNGER?

You'll see dramatic, visual examples of the Delboeuf Illusion--how easily your brain is fooled into thinking it's seeing something that's not there. You'll also find out how the brain perceives size has a direct impact on how you experience hunger.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand the principles of The Delboeuf Illusion and how it applies to food, hunger and satiation.

Goal: A greater awareness of the brain's blind spots that can be exploited to reduce hunger.

Lesson #2: ACTIVATING THE DELBOEUF ILLUSION

This step-by-step plan, recommended by neuroscientists, will activate the Delboeuf Illusion and maximize the potential to reduce hunger..

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how The Delboeuf Illusion works under different circumstances.

Skills You'll Learn: How to activate The Delboeuf Illusion and eat significantly less while feeling completely satiated.

SECTION 4: HOW THE "PORTION SIZE EFFECT" CAN BE USED TO REDUCE HUNGER

"The Portion Size Effect" is a phenomenon neuroscientists use to describe how the brain uses socially accepted portion sizes as a predictor of how much you'll eat and how satisfied you'll feel.

Example: If the portion size gets bigger you'll eat more (even if you're not any hungrier). Scientists have figured out how to reverse The Portion Size Effect's on hunger and we cover that here.

Lesson #1: WHAT IS THE "PORTION SIZE EFFECT?"

Succinct explanations and loads of examples you'll be able to relate to. Some of the counter-intuitive conclusions scientists have made about the steady increases in portion sizes will no doubt surprise you.

AIM: Understand how The Portion Size Effect works so you can neutralize it in the service of reducing hunger.

Skills You'll Learn: How to activate "The Bite Size Mechanism" produced by The Portion Size Effect, which is proven to reduce the amount of food you eat without feeling cheated or deprived.

Lesson #2 HOW TO DECREASE PORTION SIZES PAINLESSLY

Imagine being used to eating a 12 oz steak and suddenly being served 4 oz. Your startle response would go off like a howler monkey screaming against the window of a NASA rocket at liftoff.

Why?

Because drastic cuts violate habituation's golden rule: Thou shalt not awaken the startle response. Your sensors (anxiety, the threat of deprivation) activate the regulatory powers of homeostasis which then restored equilibrium by making you even hungrier so you’ll search for more food.

In this lesson, we'll investigate why it's a BAD idea to make big cuts to your portion sizes all at once and how to do it correctly.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand that you should never measure/weigh food to find out how much you should eat. Measure to understand how much you’re currently eating so you can start the process of systematic discontinuation (tapering).

Skills You'll Learn: How to use habituation and homeostasis (tapering) to reduce the amount of food you're eating without having a panic attack!

SECTION 5: CAST YOUR NEW EATING HABITS IN CEMENT

Reducing hunger requires the establishment of new eating habits. It isn't difficult but it does take time. You will inevitably go through periods where you'll forget what to do, become resistant or sabotage yourself in some way. In this section, we show you how to avoid the traps of building new eating habits by overcoming resistance, dealing with frustration and rebounding from failures.

Lesson #1: Awareness

Building new habits require you to pause and pay attention to what you’re thinking and doing. They require in-the-moment “sensors” that go off when you’re in the middle of a habit you’re trying to break, or a habit you’re trying to establish. In this lesson, you'll learn the art of "cultivating a witness state" so you can be more aware of what you're doing.

Lesson #2: Build "Emergency Reserves" For Setbacks

The latest studies in resilience show that a strategy called "Planning For Setbacks" dramatically increase accomplishment of goals. We'll show you how to apply this brilliant approach.

SECTION 5: CAST YOUR NEW EATING HABITS IN CEMENT

Quitting sugar requires the establishment of new eating habits. It isn't difficult but it does take time. You will inevitably go through periods where you'll forget what to do, become resistant or sabotage yourself in some way.

In this section, we show you how to avoid the traps of building new eating habits by overcoming resistance, dealing with frustration and rebounding from failures.

Lesson #1: Awareness

Building new habits require you to pause and pay attention to what you’re thinking and doing. They require in-the-moment “sensors” that go off when you’re in the middle of a habit you’re trying to break, or a habit you’re trying to establish. In this lesson, you'll learn the art of "cultivating a witness state" so you can be more aware of what you're doing.

Lesson #2: Build "Emergency Reserves" For Setbacks

The latest studies in resilience show that a strategy called "Planning For Setbacks" dramatically increase accomplishment of goals. We'll show you how to apply this brilliant approach.

-

Control Your Cravings

Here's a condensed outline of our CONTROL YOUR CRAVINGS class.

NOTE: All lessons end with links to the peer-reviewed studies they're based on.

SECTION 1: NATURE OF CRAVINGS & THE FORCES EXPLOITING THEM

Lesson #1 WE'RE WIRED TO CRAVE. AND OVEREAT.

Have you ever wondered why we start wanting a nibble of food and end up binging? Why do we overeat even when we don’t want to?

Few of us intend to hit food like a linebacker, yet almost all of us end up doing just that. Why? In this lesson, you’re going to learn a surprising conclusion drawn by evolutionary biologists: We are wired to overeat.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Get you to understand you don't binge on sweets because you lack self discipline or self-control. You overeat because you were designed to do so.

GOAL: Set you up to understand the next few lessons-- how the conscious brain can outsmart our instinct to overeat.

Lesson #2 ARE WE "ADDICTED" TO THE FOODS WE CRAVE?

We use the phrase "sugar addiction" in everyday conversation because our experience is eerily reminiscent of what we think of as drug addiction. You start eating, believing you're only going to eat a certain amount but once you start you can't stop.

You try to get a handle on it. You try to cut down but you repeatedly fail. There's a compulsive quality to it that can start to take on a life of its own. Despite a strong motivation to stop you're unable to get consumption under control. But here’s a question--do scientists actually believe sugar is an addictive substance? The answers will surprise you.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand sugar's properties encourage disordered eating (overeating, binging). That between the addictive nature of sugar and our wiring to overeat we need to put "guard rails" around the consumption of sweet foods and beverages

GOAL: Awareness that sugar ignites our instinct to overeat in a way that no other food does. This is necessary to understand the "guard rails" we discuss later.

Lesson #3 THE FOODS WE CRAVE ARE FORMULATED TO ADDICT US

By ordering laboratory scientists to manipulate chemicals and food substances into their highest “bliss points,” food giants can knock down the natural guard rails we have to prevent overeating.

A natural craving for cookies might compel you to eat three or four. But the way they are manufactured compels you to eat eighteen. Basically, the food industry produces food designed to make us lose control. And since three-quarters of the groceries we buy are processed food, we have a lot to lose control over. Here we discuss the science of how the industry makes processed food addictive.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Help you understand why it's so hard to control our eating around processed foods and why we have to protect ourselves from the industry’s predatory practices.

GOAL: Create a mindset shift that you can't approach eating sugary food the way you would, say, celery. Understand there are forces arrayed against you that have nothing to do with willpower and self-discipline.

SECTION 2: HOW TO WEAKEN CRAVINGS FOR UNHEALTHY FOODS

Here you’re going to learn the most effective ways to weaken or eliminate cravings for chocolate, junk food or any other unhealthy food. Centering around what neuroscientists call "food cue reactivity" you'll find proven, evidence-based techniques to liberate you from crushing cravings.

Lesson #1: "GUARD RAILS" THAT WEAKEN CRAVINGS & AVOID OVEREATING

From common sensory cues that trigger overeating to serving styles that encourage binging you'll learn how unconscious eating behaviors set the stage for a loss of control.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Awareness of particular eating patterns, habits and behaviors that contribute to a loss of control.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: How to avoid behaviors that start with cravings and lead to binging or overeating. You'll develop very specific "guard rails" that keep you safe while either entirely avoiding addictive food or allowing you to eat rational portions without wanting more.

Lesson #2: HOW TO CREATE MORE FRICTION AROUND ADDICTIVE FOODS

Again, we cannot approach a donut the way we would an apple. Here we investigate a concept known as "friction" that's proven to eliminate or significantly reduce overeating.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Awareness of how creating "friction" around addictive foods can practically guarantee you won't overeat.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: Dozens of tactics and strategies designed to stop you from overeating, not from enjoying food you love. They are a recognition that our instinct to overeat, the addictive properties of processed foods, and the industry’s exploitation of our cravings all compel us to approach these unhealthy foods differently than we do healthy foods.

SECTION 3: HOW TO MANAGE CRAVINGS

Here you’re going to learn two delayed gratification techniques that cut out a tremendous number of calories while preserving your ability to eat whatever you want. How is that possible? By replacing the current framework you're using ("Yes, I will indulge/No, I will not" with a better one ("Yes, I will indulge/ No, I will POSTPONE").

Lesson #1: THE DELAYED GRATIFICATION TECHNIQUES YOU'RE CURRENTLY USING ARE COMPLETELY FLAWED.

A neuroscientific critique of the utter uselessness of traditional delayed gratification techniques advocated by dieting ("I'll give up this burger so I can lose weight/get healthier"). When you find out why this type of approach has a 95% failure rate you'll never use it again.

AIM: Awareness of how useless and damaging traditional delayed gratification techniques are and why they almost always fail completely. For example, studies show that intellectual abstractions ("If I give up this burger today, Ill get thinner sometime in the future") can rarely compete with visceral emotions (the intensity of the look and smell of that burger!).

Goal: Convince you to give up using dieting's version of delayed gratification and embrace neuroscience's far more effective version (which you'll learn in the next lesson).

Lesson #2: NEUROSCIENCE'S PREFERRED DELAYED GRATIFICATION TECHNIQUE

This method avoids the corrosive "intellectual abstraction vs visceral pleasure" dynamic riddling traditional delayed gratification techniques and replaces it with something far more powerful. Combining mindfulness with can't lose choices, this 5-second technique was voted "favorite technique" by hundreds of our students.

AIM: Understand the concept behind the PAUSE-RATE-DECIDE technique, why it's so powerful and the benefits it brings.

Goal: Instead of resisting cravings, you'll see the wisdom of tuning into them, and working with rather than against them.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: How to apply the PAUSE-RATE-DECIDE technique right before every snack or meal.

SECTION 4: A SECOND DELAYED GRATIFICATION TECHNIQUE DEVELOPED BY NEUROSCIENTISTS

How can the French eat anything they want and not gain weight? By managing their cravings differently than we do. Our second delayed gratification technique was inspired by anthropological research into foodie cultures in France, Italy and Japan. What they found was completely counter to the dieting ethos so prevalent in the U.S.

These cultures use pleasure, not deprivation to manage their cravings. Thus, our second delayed gratification system doesn't confront a craving with sacrifice ("Should I give up these fries so I can lose weight/get healthier sometime in the future?").

Instead, it confronts it the way the French do--with PLEASURE ("Should I eat these fries or wait until I can find a better version of them?")

Lesson #1: HOW THE FRENCH MANAGE CRAVINGS--AND HOW YOU CAN TOO

You'll see studies showing when you base food decisions on higher and higher levels of pleasure you become habituated to higher and higher levels of satisfaction. Over time you become less and less satisfied with the merely pleasurable, which is what junk food is, and insist on the mouth-watering.

And when that happens, you start cutting out junk foods, not because they’re bad for you, but because they no longer meet your minimum requirements for pleasure. THIS is how epicurean societies like the French manage their cravings and eat what they want without gaining weight.

AIM: Understand the epicurean mindset that the pursuit of pleasure, not dieting and deprivation, is the path to weight loss.

GOAL: Convince you to give up dieting and its corrosive denial of pleasure in favor of becoming a pleasure junkie who gives up volume for quality.

Lesson #2: TRAIN YOUR TASTE BUDS TO REJECT LOW-PLEASURE EATING

This lesson shows you how to "put your taste buds in rehab" so that you reject low-pleasure eating (a good deal of the American diet) in favor of high-pleasure consumption. Again, studies show that pleasure junkies gladly reject junk food (low pleasure eating) and wait for a high-pleasure eating opportunity. Since high-pleasure food is harder to come by you naturally eliminate a significant amount of calories from your diet.

AIM: Understand the importance of raising the level of pleasure you get out of food. Example: You'll get way more pleasure out of fresh-baked cookies than processed, packaged ones).

GOAL: Train your taste buds to reject low-pleasure foods in favor of food that sends you into a rapture, knowing it will reduce the volume of food you eat in exchange for more pleasure.

Lesson #3: A NEUROSCIENTIFIC TECHNIQUE THAT TRAINS YOUR TASTE BUDS TO HAPPILY REJECT LOW PLEASURE EATING.

Would you sacrifice a mediocre meal for an excellent one? Would you turn down a snack that sends you into the doldrums for a snack that sent you to the moon? Of course you would! Maximizing pleasure is a driving force of human nature --and the engine that drives this lesson.

AIM: Understand the concept behind the technique known as Postponement For The Rapture. It is the delayed gratification tool you'll use to adopt a new mindset: Pleasure is more important than volume.

GOAL: To be far more motivated by smaller amounts of high-pleasure food than larger amounts of mediocre food.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: The ability to instantly--and gladly--give up low-pleasure eating in favor of intensely pleasurable eating.

SECTION 5: CAST YOUR NEW EATING HABITS IN CEMENT

Reducing hunger requires the establishment of new eating habits. It isn't difficult but it does take time. You will inevitably go through periods where you'll forget what to do, become resistant or sabotage yourself in some way. In this section, we show you how to avoid the traps of building new eating habits by overcoming resistance, dealing with frustration and rebounding from failures.

Lesson #1: Awareness

Building new habits require you to pause and pay attention to what you’re thinking and doing. They require in-the-moment “sensors” that go off when you’re in the middle of a habit you’re trying to break, or a habit you’re trying to establish. In this lesson, you'll learn the art of "cultivating a witness state" so you can be more aware of what you're doing.

Lesson #2: Build "Emergency Reserves" For Setbacks

The latest studies in resilience show that a strategy called "Planning For Setbacks" dramatically increase accomplishment of goals. We'll show you how to apply this brilliant approach.

-

Stop Overeating

Here's a condensed outline of our STOP OVEREATING class.

NOTE: All lessons end with links to the peer-reviewed studies they're based on.

SECTION 1: THE NATURE OF OVEREATING & THE FORCES EXPLOITING IT

Lesson #1 WE'RE WIRED TO OVEREAT.

Have you ever wondered why we start wanting a nibble of food and end up binging? Why do we overeat even when we don’t want to?

Few of us intend to hit food like a linebacker, yet almost all of us end up doing just that. Why? In this lesson, you’re going to learn a surprising conclusion drawn by evolutionary biologists: We are wired to overeat.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Get you to understand you don't binge on sweets because you lack self discipline or self-control. You overeat because you were designed to do so.

GOAL: Set you up to understand the next few lessons-- how the conscious brain can outsmart our instinct to overeat.

Lesson #2 ARE WE "ADDICTED" TO THE FOODS WE CRAVE?

We use the phrase "sugar addiction" in everyday conversation because our experience is eerily reminiscent of what we think of as drug addiction. You start eating, believing you're only going to eat a certain amount but once you start you can't stop.

You try to get a handle on it. You try to cut down but you repeatedly fail. There's a compulsive quality to it that can start to take on a life of its own. Despite a strong motivation to stop you're unable to get consumption under control. But here’s a question--do scientists actually believe sugar is an addictive substance? The answers will surprise you.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand sugar's properties encourage disordered eating (overeating, binging). That between the addictive nature of sugar and our wiring to overeat we need to put "guard rails" around the consumption of sweet foods and beverages

GOAL: Awareness that sugar ignites our instinct to overeat in a way that no other food does. This is necessary to understand the "guard rails" we discuss later.

Lesson #3 PROCESSED FOOD IS DESIGNED TO MAKE US OVEREAT

By ordering laboratory scientists to manipulate chemicals and food substances into their highest “bliss points,” food giants can knock down the natural guard rails we have to prevent overeating.

A natural craving for cookies might compel you to eat three or four. But the way they are manufactured compels you to eat eighteen. Basically, the food industry produces food designed to make us lose control.

And since three-quarters of the groceries we buy are processed food, we have a lot to lose control over. Here we discuss the science of how the industry makes processed food addictive.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Help you understand why it's so hard to control our eating around processed foods and why we have to protect ourselves from the industry’s predatory practices.

GOAL: Create a mindset shift that you can't approach eating sugary food the way you would, say, celery. Understand there are forces arrayed against you that have nothing to do with willpower and self-discipline.

SECTION 2: HOW TO WEAKEN CRAVINGS FOR UNHEALTHY FOODS

Here you’re going to learn the most effective ways to weaken or eliminate cravings for chocolate, junk food or any other unhealthy food. Centering around what neuroscientists call "food cue reactivity" you'll find proven, evidence-based techniques to liberate you from crushing cravings.

Lesson #1: "GUARD RAILS" THAT WEAKEN CRAVINGS & AVOID OVEREATING

From common sensory cues that trigger overeating to serving styles that encourage binging you'll learn how unconscious eating behaviors set the stage for a loss of control.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Awareness of particular eating patterns, habits and behaviors that contribute to a loss of control.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: How to avoid behaviors that start with cravings and lead to binging or overeating. You'll develop very specific "guard rails" that keep you safe while either entirely avoiding addictive food or allowing you to eat rational portions without wanting more.

Lesson #2: HOW TO CREATE MORE FRICTION AROUND ADDICTIVE FOODS

Again, we cannot approach a donut the way we would an apple. Here we investigate a concept known as "friction" that's proven to eliminate or significantly reduce overeating.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Awareness of how creating "friction" around addictive foods can practically guarantee you won't overeat.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: Dozens of tactics and strategies designed to stop you from overeating, not from enjoying food you love. They are a recognition that our instinct to overeat, the addictive properties of processed foods, and the industry’s exploitation of our cravings all compel us to approach these unhealthy foods differently than we do healthy foods.

SECTION 3: HOW TO REDUCE OR ELIMINATE STRESS EATING

Lesson #1 Quick Mindfulness Meditations and Breathwork Proven To Stop Stress Eating

There are dozens of research studies showing that certain mindful meditations and strategic breathwork are highly effective in stopping or reducing stress eating. In this lesson, you'll learn what they are and how to use them to maximum effect. Surprising finding: None of these techniques take longer than 5 minutes.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how investing as little as 5 minutes a day can significantly lower or eliminate overeating.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: How to achieve a calm, relaxed state that can prevent overeating.

Lesson #2: WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU’RE ABOUT TO STRESS EAT

In this lesson, you’re going to learn some simple tools you can use when the urge to stress eat comes over you. Developed out of pioneering psychologist Walter Mischel's work on "The Marshmallow Experiments," these techniques are remarkably effective at heading off a binge.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how the power of techniques like "self-distancing" and others can radically reduce urges to binge.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: How to apply these techniques to your particular situations.

SECTION 4: HOW TO STOP THE SELF-SABOTAGE

Overeating is easy to do if you don't know how full you're getting, if you eat while you're distracted or look at your environment instead of your self-assessments to determine when we should stop eating. All of these amount to self-sabotage. In these lessons, you'll hear advice from neuroscientists on how to reverse the eating habits and patterns that keep the sabotage in place.

Lesson #1 STOP ENCOURAGING YOURSELF TO OVEREAT

In this lesson you'll learn how "Distracted Eating" (eating while you're watching tv or scrolling through your smartphone) or "Package Eating" (eating out of a bag or box) force the brain to use environmental factors (the show ends, the smartphone battery goes out) to stop eating rather than internal satiety cues.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how the brain's ability to determine satiety (normal eating) is radically altered by unhealthy eating habits, which inevitably lead to overeating.

GOAL: Stop sabotaging yourself; stop doing the things neuroscientists say promote overeating.

Skills You'll Learn: Techniques that avoid forcing the brain to look outside the body for signs to stop eating. Methods that produce the kind of mindfulness that makes overeating almost impossible.

Lesson #2 HOW A SIMPLE MATH TRICK CAN HELP YOU EAT NORMALLY

Ever notice how often you underestimate how full you are? For example, you decide you have room for dessert so you eat it but 20 minutes later you feel STUFFED. What went wrong? In this lesson, you'll understand why we're so bad at estimating our fullness and what we can do about it.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand why neuroscientists believe we constantly underestimate how full we are.

GOAL: Learn how to use a simple math trick that can give you nearly 100% accuracy.

Skills You'll Learn: How to apply this math trick at every eating opportunity--breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks.

SECTION 4: HOW TO EAT LESS WITHOUT FEELING DEPRIVED

It's possible to feel just as satisfied eating a smaller portion of food than a larger one. This might sound ridiculous to anyone used to eating Avalanche Burgers or drinking 64 oz Big Gulps, but science begs to differ.

In these lessons you'll see how easily you can start eating a lot less without leaving the table hungry.

Lesson #1 SENSORY SPECIFIC SATIETY HELPS YOU EAT LESS WITHOUT FEELING DEPRIVED.

In this lesson, we'll explain a concept called "sensory specific satiety," a phenomenon we all experience when we eat: We receive less pleasure with each bite. That's why the first slice of pizza is WOW and the fourth slice is MEH.

Neuroscientists have proved, in dozens of studies, that sensory specific satiety can be exploited to help people eat a lot less food and feel completely satisfied.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand the physiological underpinnings of sensory specific satiety.

GOAL: Understand its specific ability to help us eat less.

Lesson #2 HOW TO USE SENSORY SPECIFIC SATIETY ON SNACKS--BOTH SALTY AND SWEET

Studies show that people eat less when they pay more attention to their taste buds (sensory specific satiety--the declining pleasure of food) than their stomachs (how full they're getting).

In this lesson, you'll learn how these studies were conducted and how to apply them to your own eating.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Learn the central tenets of these studies--"Eat until the pleasure of the flavors subside."

SKILLS YOU'll LEARN: How to apply the gist of these studies to your own eating so you can harvest the same benefits--eating less and feeling satisfied.

SECTION 5: HOW RITUALS STOP YOU FROM OVEREATING

Perhaps one of the most surprising findings in the neuroscience literature is the power that rituals have to stop you from overeating. In fact, the research shows that rituals are instrumental to sustained weight loss. In these lessons you'll find out why and how you can incorporate rituals in your own eating.

Lesson #1 HOW RITUALS STOP PEOPLE FROM OVEREATING SNACKS.

In this lesson, you'll find out about a famous Harvard experiment that showed rituals can help you eat less and enjoy it more. We'll re-enact the study in your own snacking so you can test-drive the concept and see the influence rituals can have on your eating.

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand why rituals stop overeating, enhance enjoyment and create a deeper appreciation for food..

GOAL: To incorporate rituals into your daily habits before you eat any snack.

Lesson #2 HOW TO USE RITUALS BEFORE & DURING MEALS TO STOP OVEREATING

Experts who study the role of ritual in weight loss say every meal, taken alone or with others, should have a conscious beginning, middle, and end. Here you'll find out what they are and the best rituals that fit your lifestyle.

Please note that studies show rituals are most effective when they're fairly short, so you time-pressed folks....don't worry!

LESSON TAKEAWAYS

AIM: Understand how rituals are a hallmark of mindful eating and they have a long history of producing weight loss.

GOAL: Find out which rituals (we list a lot of them) work best for you.

SKILLS YOU'LL LEARN: Best practices for meal and pre-meal rituals to maximize weight loss, stop overeating and enjoy your food more.

SECTION 6: CAST YOUR NEW EATING HABITS IN CEMENT

Ending overeating and binging requires the establishment of new eating habits. It isn't difficult but it does take time. You will inevitably go through periods where you'll forget what to do, become resistant or sabotage yourself in some way. In this section, we show you how to avoid the traps of building new eating habits by overcoming resistance, dealing with frustration and rebounding from failures.

Lesson #1: Awareness

Building new habits require you to pause and pay attention to what you’re thinking and doing. They require in-the-moment “sensors” that go off when you’re in the middle of a habit you’re trying to break, or a habit you’re trying to establish. In this lesson, you'll learn the art of "cultivating a witness state" so you can be more aware of what you're doing.

Lesson #2: Build "Emergency Reserves" For Setbacks

The latest studies in resilience show that a strategy called "Planning For Setbacks" dramatically increase accomplishment of goals. We'll show you how to apply this brilliant approach.

NO OBLIGATION TRIAL!

During our FREE trial, you'll have access to a handful of lessons that will change your eating habits for lasting results.

You'll also be able to ask questions and get feedback from our team of experts.

If you decide you want to continue after the trial, you can sign up for our full course.

Try Neuroslim for free with our risk-free, no-obligation trial. No credit card required, no money upfront. Just sign up and start changing the habits that caused your weight gain!

Our Free Gift To You!

Want to see an example of our neuroscience techniques? Download our free guide to quitting sugar. Just plug in your email address and you'll get a download link.

Got it! Check your email for the download link.

Oops, there was an error.

Please try again later.

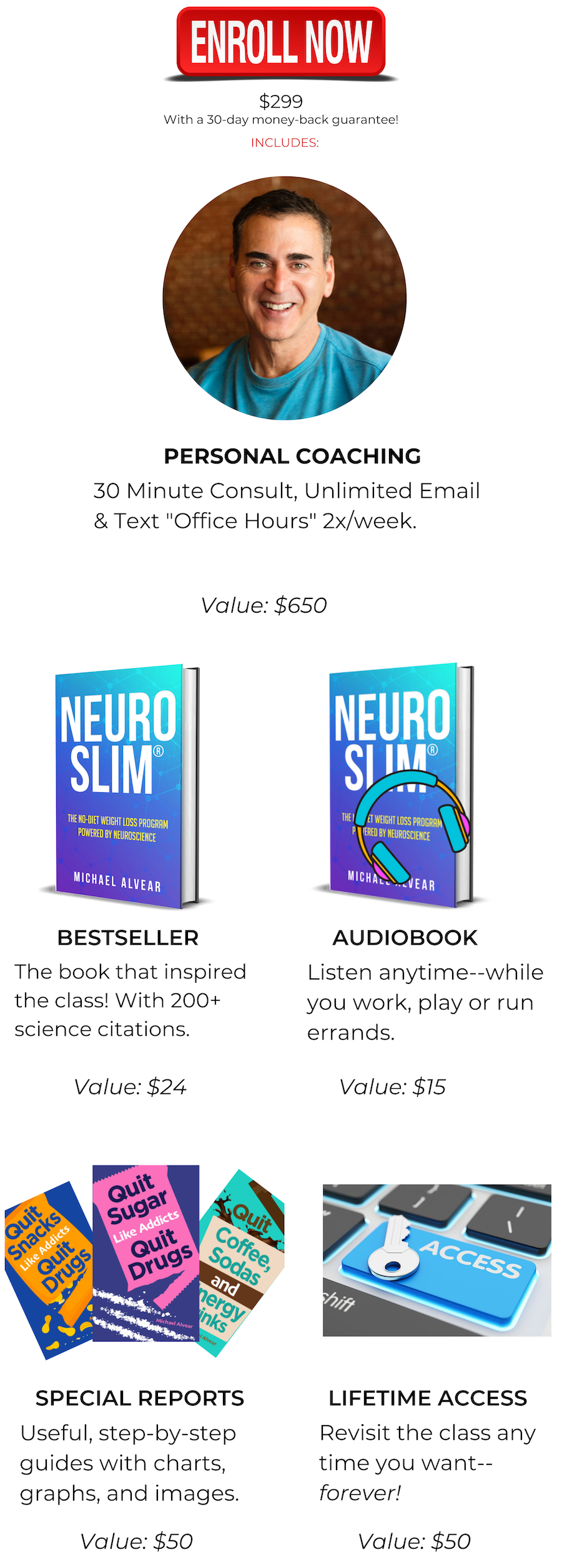

Includes FREE Personal Coaching!

Your class includes a 30-minute personal coaching call with Michael Alvear, the founder of Neuroslim.

With unlimited email support and access to his Facebook "Office Hours" where you can ask questions, you'll never feel lost and alone.

No other class offers this kind of personal attention. We won't leave you to figure it out on your own. We'll be with you every step of the way.

About The Founder Of Neuroslim

Author & Writer

Michael Alvear is the author of four weight loss books: Eat It Later, Grand Theft Weight Loss, Not Tonight Dear I Feel Fat and Neuroslim: The No-Diet Weight Loss Program Powered By Neuroscience.

Thought Leader

Michael's research and observations have been published in WebMD, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and The Huffington Post. His commentaries have aired on NPR's All Things Considered.

Researcher

Michael has been studying and publishing research on weight loss for the last two decades.

WHY I CREATED A SCIENCE-BACKED ALTERNATIVE TO DIETING

As a weight loss researcher and author, I wanted to offer an alternative to the cruelty of deprivation dieting. So I instructed my team to search through thousands of peer-reviewed studies by leading neuroscientists, evolutionary biologists, and behavioral psychologists. We found a treasure-trove of published but unpublicized research proving it’s neuroscience, not dieting, that holds the key to permanent weight loss.

We took the most important discoveries in the scientific literature and created a logical, easy-to-implement weight loss program we call NeuroSlim.®

Every Technique Backed By Studies…

Every lesson in the class ends with a list of academic citations (including links) so you can see which scientists developed the lesson’s insights, tools and techniques, how these scientists came to their conclusions and which academic journals published their works.

I did this to show you how rooted the lessons are in science, to help you verify the lessons’ information, and find out more about the subject if you want to research it further.

…And My Personal Attention

The NeuroSlim® program also includes access to me, through a multi-media package of personal coaching (phone, Zoom, email and social media groups).

The evidence-based insights and techniques you’re going to learn in the class are easy but, unless you’re a neuroscientist, you’ve probably never heard of them. That’s where I come in. Got a question? Call me. Need clarification? Email me? Want support? Let’s chat during my Facebook “Office Hours.”

No Medicine, No Supplements, No Vitamins, No Dieting.

I am on a research-heavy, evidence-based mission to stop the toxic mentality of dieting promoted by what I call the Diet Weight Loss Industrial Complex.

The scientific literature is filled with studies showing you don’t need to diet to get to a healthy weight. The evidence is everywhere--in research portals like Google Scholar, medical databases like PubMed, science libraries like the Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews and academic journals like The New England Journal of Medicine.

NeuroSlim® Is Not A Diet

It does not traffic in recipes, meal plans, or nutritional advice. There isn’t a list of foods to eat or avoid.

It isn’t therapy or a support group, either. You will not be asked to “process” your feelings about food, revisit formative experiences with family meals or explore your body image issues.

NeuroSlim® is a portal for remodeling your eating habits, reducing unnecessary hunger, quitting sugar, weakening cravings for fattening food and developing intense cravings for healthy ones. All through evidence-based techniques developed by the finest minds in neuroscience.

YOU’VE TRIED DIETING.

TIME FOR SOMETHING NEW.

The Neuroslim Class

$299

FIVE STARS!

I used to eat half a dozen donuts at a sitting but after taking Neuroslim I'm completely satisfied with 1 or 2. There's no diet that ever taught me how to do that!

With diets the weight came off then came back. With Neuroslim, the weight came off and stayed off.

I didn't have to deprive myself of foods I love (donuts!) or spend hours at the gym. There's nothing magical about the process--it was plain, proven science. I look at myself in the mirror these days and cannot believe the difference. FIVE STARS!

Miranda Folsom

Chicago

I'll Never Diet Again.

I never thought I'd ever see a thinner, healthier version of myself in the mirror--certainly not without a lot of hard work, willpower or discipline.

Neuroslim requires none of these because the weight loss comes from changing habits, not keeping yourself away from delicious food.

Losing weight with Neuroslim took no effort. I took the class a year ago and the weight is

still off.

Marco Salazar

Dallas

Completely Changed The Way I Eat.

I lost 20 lbs two years ago with Neuroslim and the weight never came back.

I simply didn't believe there was a way to lose weight without dieting but now I'm a complete believer. Throw away your diet books, this class is the only thing you need to lose weight.

Ruth Taylor

Portland, OR

A $1,088 Value for $299!

Three Payment Plans To Choose From:

QUESTIONS? CLARIFICATIONS?

Call Us

706-395-5918

Monday-Friday 11a - 7p EST

-

Research Studies

Weight Loss Research Studies

Informing The NeuroSlim Online Weight Loss Program

The NeuroSlim® research team analyzed thousands of peer-reviewed studies, extracted their most important discoveries and turned them into an easy-to-follow weight loss program.

We used over 200 academic studies to form the basis of our program. These peer-reviewed studies were conducted by leading neuroscientists, evolutionary biologists, behavioral psychologists, social psychologists, anthropologists, physiologists and Addiction Medicine specialists.

We've provided this list of citations so you can see which scientists developed the insights, tools and techniques in the NeuroSlim® program, how these scientists came to their conclusions and which academic journals published their works.

You can find these studies in research portals like Google Scholar, medical databases like PubMed, science libraries like the Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews and academic journals like The New England Journal of Medicine

Our list of citations will help you verify our assertions and help you find out more about each subject if you want to research them further.

Here's the best part: We've provided pull-out quotes from the conclusions of each study so you can get an at-a-glance distillation of these dense scientific papers.

Here's the second best part: We've provided links to every one of the studies! This provides a tremendous shortcut, giving you immediate access to the data-rich insights you'll find in our program.

HOW FOOD AESTHETICS INFLUENCES APPETITE

Koyama, K. I., Amitani, H., Adachi, R., Morimoto, T., Kido, M., Taruno, Y., Ogata, K., Amitani, M., Asakawa, A., & Inui, A. (2016). Good appearance of food gives an appetizing impression and increases cerebral blood flow of frontal pole in healthy subjects. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 67(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.3109/09637486.2015.1118618

Quote: Good appearance of food gives an appetizing impression and increases cerebral blood flow of frontal pole in healthy subjects.

Devina Wadhera, & Elizabeth D. Capaldi-Phillips. (2014). A review of visual cues associated with food on food acceptance and consumption, Eating Behaviors, Volume 15, Issue 1, Pages 132-143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.11.003.

Quote: All together, these studies show that color can affect perceived flavor, odor, and taste intensity of foods which can then affect food intake.

Wu, C., Zhu, H., Huang, C., Liang, X., Zhao, K., Zhang, S., He, M., Zhang, W., & He, X. (2022). Does a beautiful environment make food better - The effect of environmental aesthetics on food perception and eating intention. Appetite, 175, 106076. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106076

Quote: This research also explored the mediating role of emotion in the relationship between environmental aesthetics and food perception and found a significant mediating relationship. In conclusion, environmental aesthetics play an important role in food perception, and these findings provide insights into increasing positive food perception in daily life.

ENVIRONMENTAL FOOD CUES AND THEIR EFFECT ON FOOD INTAKE

Suzanne Higgs, & Jason Thomas. (2016), Social influences on eating, Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, Volume 9, Pages 1-6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.10.005

Quote: Norm matching involves processes such as synchronisation of eating actions, consumption monitoring and altered food preferences. There is emerging evidence that social eating norms may play a role in the development and maintenance of obesity.

Anita Jansen, Nicole Theunissen, Katrien Slechten, Chantal Nederkoorn, Brigitte Boon, Sandra Mulkens, & Anne Roefs, (2003), Overweight children overeat after exposure to food cues, Eating Behaviors, Volume 4, Issue 2, Pages 197-209, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00011-4

Quote: The data indeed show that overweight children do not regulate their food intake like normal-weight children do. Normal-weight children eat less after having eaten a preload and after intense exposure to the smell of tasty food, whereas the overweight children do not lessen their intake after confrontation with both food cues. They even eat marginally more after the intense exposure to the smell of tasty food.

Fedoroff, I. D., Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (1997). The effect of pre-exposure to food cues on the eating behavior of restrained and unrestrained eaters. Appetite, 28(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1006/appe.1996.0057

Quote: These findings suggest that restrained eaters are more sensitive and reactive to food cues than are unrestrained eaters. The food cues appeared to generate an appetitive urge to eat in restrained eaters.

Coelho, J. S., Jansen, A., Roefs, A., & Nederkoorn, C. (2009). Eating behavior in response to food-cue exposure: examining the cue-reactivity and counteractive-control models. Psychology of addictive behaviors : journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 23(1), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013610

Quote: Participants with high weight-related concerns who attended to a food cue ate more than did both those with high weight-related concerns in the control condition and those with low weight-related concerns in the attended-cue condition.

Rolls, B., Rowe, E., & Rolls, E. (1982). How flavour and appearance affect human feeding. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 41(2), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS19820019

Quote: The flavour and shape of foods can affect both the amount of food eaten and the subjective responses to foods. We have found that the successive presentation of foods which vary just in flavour or shape leads to a significantly greater intake in a meal than the presentation of just one flavour or shape.

SENSORY SPECIFIC SATIETY

Wilkinson, L. L., & Brunstrom, J. M. (2016). Sensory specific satiety: More than 'just' habituation?. Appetite, 103, 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.04.019

Quote: Broadly, they support an explanation of SSS based on habituation or stimulus specificity rather than top-down influences based on the availability of uneaten foods.

Raynor, H. A., & Epstein, L. H. (2001). Dietary variety, energy regulation, and obesity. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.325

Quote: Animal and human studies show that food consumption increases when there is more variety in a meal or diet and that greater dietary variety is associated with increased body weight and fat. A hypothesized mechanism for these findings is sensory-specific satiety

González, A., Recio, S. A., Sánchez, J., Gil, M., & de Brugada, I. (2018). Effect of exposure to similar flavours in sensory specific satiety: Implications for eating behaviour. Appetite, 127, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.05.015

Quote: The results suggest that easy and continuous access to a high variety of similar unhealthy foods might have long-term effects on food consumption, and highlight a potential mechanism linking obesogenic environments with dietary habits.

Sashie Abeywickrema, Indrawati Oey, & Mei Peng, (2022), Sensory specific satiety or appetite? Investigating effects of retronasally-introduced aroma and taste cues on subsequent real-life snack intake, Food Quality and Preference, Volume 100.

EXERCISE’S EFFECT ON EMOTIONAL EATING

Annesi, J. J., & Eberly, A. A. (2022). Sequential Mediation of the Relation of Increased Physical Activity and Weight Loss by Mood and Emotional Eating Changes: Community-Based Obesity Treatment Development Guided by Behavioral Theory. Family & community health, 45(3), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000331

Quote: Paths from changes in physical activity → mood → emotional eating → weight were significant, with no alternate path reaching significance.

Annesi J. J. (2021). Effects of Increased Exercise on Propensity for Emotional Eating Through Associated Psychological Changes. Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 53(11), 944–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2021.07.003

Quote: Changes in self-regulation (95% confidence interval [CI], -0.010 to -0.002), mood (95% CI, -0.011 to -0.003), and body image (95% CI, -0.011, -0.002) significantly mediated the exercise-emotional eating relationship.

Annesi, J. J., & Mareno, N. (2015). Indirect effects of exercise on emotional eating through psychological predictors of weight loss in women. Appetite, 95, 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.07.012

Quote: In a multiple mediation analysis, changes in self-regulation, self-efficacy, and mood significantly mediated the relationship between changes in exercise and emotional eating.

Annesi J. J. (2020). Sequential Changes Advancing from Exercise-Induced Psychological Improvements to Controlled Eating and Sustained Weight Loss: A Treatment-Focused Causal Chain Model. The Permanente journal, 24, 19.235. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/19.235

Quote: The model presents an evidence-based explanation of the exercise-weight loss association through psychosocial mechanisms.

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SLEEP AND EMOTIONAL/STRESS EATING

López-Cepero, A., Frisard, C., Mabry, G., Spruill, T., Mattei, J., Austin, S. B., Lemon, S. C., & Rosal, M. C. (2022). Association between poor sleep quality and emotional eating in US Latinx adults and the mediating role of negative emotions. Behavioral sleep medicine, 1–10. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2022.2060227

Quote: Poor sleep quality was associated with high EE (emotional eating) in US Latinx adults and negative emotions partially mediated this relationship.

Zerón-Rugerio, M. F., Hernáez, Á., Cambras, T., & Izquierdo-Pulido, M. (2022). Emotional eating and cognitive restraint mediate the association between sleep quality and BMI in young adults. Appetite, 170, 105899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105899

Quote: In conclusion, young adults with poor sleep quality are more likely to deal with negative emotions with food, which, in turn, could be associated with higher cognitive restraint, becoming a vicious cycle that has a negative impact on body weight.

Barragán, R., Zuraikat, F. M., Tam, V., Scaccia, S., Cochran, J., Li, S., Cheng, B., & St-Onge, M. P. (2021). Actigraphy-Derived Sleep Is Associated with Eating Behavior Characteristics. Nutrients, 13(3), 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030852

Quote: Results of this analysis suggest that the association of poor sleep on food intake could be exacerbated in those with eating behavior traits that predispose to overeating, and this sleep-eating behavior relation may be sex-dependent.

Dweck, J. S., Jenkins, S. M., & Nolan, L. J. (2014). The role of emotional eating and stress in the influence of short sleep on food consumption. Appetite, 72, 106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.001

Quote: The results suggest that the relationship between short sleep and elevated food consumption exists in those who are prone to emotional eating.

Annesi, J. J., & Marti, C. N. (2011). Path analysis of exercise treatment-induced changes in psychological factors leading to weight loss. Psychology & health, 26(8), 1081–1098. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2010.534167

Quote: Associations of psychological effects linked to exercise programme participation with predictors of appropriate eating and weight loss were found, and may inform theory, research and treatments.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2022.104612

Quote: Our findings reveal that exposure to retronasally introduced vanilla aroma, and the sweet taste can induce daylong sensory-specific effects. Specifically, pre-exposure to sweet-associated aroma (i.e., vanillin) and taste (i.e., sucralose) stimuli decrease sensory-congruent (i.e., sweet), but increase sensory-incongruent (i.e., non-sweet) snack intake throughout the day. Overall, the study suggests that sensory exposure may have lasting temporal effects on eating behaviour

MEDITATION/MINDFULNESS IMPACT ON OVEREATING

Katterman, S. N., Kleinman, B. M., Hood, M. M., Nackers, L. M., & Corsica, J. A. (2014). Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: a systematic review. Eating behaviors, 15(2), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.01.005

Quote: Results suggest that mindfulness meditation effectively decreases binge eating and emotional eating in populations engaging in this behavior; evidence for its effect on weight is mixed.